Epimorphism

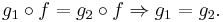

In category theory, an epimorphism (also called an epic morphism or, colloquially, an epi) is a morphism f : X → Y which is right-cancellative in the sense that, for all morphisms g1, g2 : Y → Z,

Epimorphisms are analogues of surjective functions, but they are not exactly the same. The dual of an epimorphism is a monomorphism (i.e. an epimorphism in a category C is a monomorphism in the dual category Cop).

Many authors in abstract algebra and universal algebra define an epimorphism simply as an onto or surjective homomorphism. Every epimorphism in this algebraic sense is an epimorphism in the sense of category theory, but the converse is not true in all categories. In this article, the term "epimorphism" will be used in the sense of category theory given above. For more on this, see the section on Terminology below.

Contents |

Examples

Every morphism in a concrete category whose underlying function is surjective is an epimorphism. In many concrete categories of interest the converse is also true. For example, in the following categories, the epimorphisms are exactly those morphisms which are surjective on the underlying sets:

- Set, sets and functions. To prove that every epimorphism f: X → Y in Set is surjective, we compose it with both the characteristic function g1: Y → {0,1} of the image f(X) and the map g2: Y → {0,1} that is constant 1.

- Rel, sets with binary relations and relation preserving functions. Here we can use the same proof as for Set, equipping {0,1} with the full relation {0,1}×{0,1}.

- Pos, partially ordered sets and monotone functions. If f : (X,≤) → (Y,≤) is not surjective, pick y0 in Y \ f(X) and let g1 : Y → {0,1} be the characteristic function of {y | y0 ≤ y} and g2 : Y → {0,1} the characteristic function of {y | y0 < y}. These maps are monotone if {0,1} is given the standard ordering 0 < 1.

- Grp, groups and group homomorphisms. The result that every epimorphism in Grp is surjective is due to Otto Schreier (he actually proved more, showing that every subgroup is an equalizer using the free product with one amalgamated subgroup); an elementary proof can be found in (Linderholm 1970).

- FinGrp, finite groups and group homomorphisms. Also due to Schreier; the proof given in (Linderholm 1970) establishes this case as well.

- Ab, abelian groups and group homomorphisms.

- K-Vect, vector spaces over a field K and K-linear transformations.

- Mod-R, right modules over a ring R and module homomorphisms. This generalizes the two previous examples; to prove that every epimorphism f: X → Y in Mod-R is surjective, we compose it with both the canonical quotient map g 1: Y → Y/f(X) and the zero map g2: Y → Y/f(X).

- Top, topological spaces and continuous functions. To prove that every epimorphism in Top is surjective, we proceed exactly as in Set, giving {0,1} the indiscrete topology which ensures that all considered maps are continuous.

- HComp, compact Hausdorff spaces and continuous functions. If f: X → Y is not surjective, let y in Y-fX. Since fX is closed, by Urysohn's Lemma there is a continuous function g1:Y → [0,1] such that g1 is 0 on fX and 1 on y. We compose f with both g1 and the zero function g2: Y → [0,1].

However there are also many concrete categories of interest where epimorphisms fail to be surjective. A few examples are:

- In the category of monoids, Mon, the inclusion map N → Z is a non-surjective epimorphism. To see this, suppose that g1 and g2 are two distinct maps from Z to some monoid M. Then for some n in Z, g1(n) ≠ g2(n), so g1(-n) ≠ g2(-n). Either n or -n is in N, so the restrictions of g1 and g2 to N are unequal.

- In the category of rings, Ring, the inclusion map Z → Q is a non-surjective epimorphism; to see this, note that any ring homomorphism on Q is determined entirely by its action on Z, similar to the previous example. A similar argument shows that the natural ring homomorphism from any commutative ring R to any one of its localizations is an epimorphism.

- In the category of commutative rings, a finitely generated homomorphism of rings f : R → S is an epimorphism if and only if for all prime ideals P of R, the ideal Q generated by f(P) is either S or is prime, and if Q is not S, the induced map Frac(R/P) → Frac(S/Q) is an isomorphism (EGA IV 17.2.6).

- In the category of Hausdorff spaces, Haus, the epimorphisms are precisely the continuous functions with dense images. For example, the inclusion map Q → R, is a non-surjective epimorphism.

The above differs from the case of monomorphisms where it is more frequently true that monomorphisms are precisely those whose underlying functions are injective.

As to examples of epimorphisms in non-concrete categories:

- If a monoid or ring is considered as a category with a single object (composition of morphisms given by multiplication), then the epimorphisms are precisely the right-cancellable elements.

- If a directed graph is considered as a category (objects are the vertices, morphisms are the paths, composition of morphisms is the concatenation of paths), then every morphism is an epimorphism.

Properties

Every isomorphism is an epimorphism; indeed only a right-sided inverse is needed: if there exists a morphism j : Y → X such that fj = idY, then f is easily seen to be an epimorphism. A map with such a right-sided inverse is called a split epi. In a topos, a map that is both a monic morphism and an epimorphism is an isomorphism.

The composition of two epimorphisms is again an epimorphism. If the composition fg of two morphisms is an epimorphism, then f must be an epimorphism.

As some of the above examples show, the property of being an epimorphism is not determined by the morphism alone, but also by the category of context. If D is a subcategory of C, then every morphism in D which is an epimorphism when considered as a morphism in C is also an epimorphism in D; the converse, however, need not hold; the smaller category can (and often will) have more epimorphisms.

As for most concepts in category theory, epimorphisms are preserved under equivalences of categories: given an equivalence F : C → D, then a morphism f is an epimorphism in the category C if and only if F(f) is an epimorphism in D. A duality between two categories turns epimorphisms into monomorphisms, and vice versa.

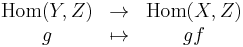

The definition of epimorphism may be reformulated to state that f : X → Y is an epimorphism if and only if the induced maps

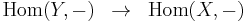

are injective for every choice of Z. This in turn is equivalent to the induced natural transformation

being a monomorphism in the functor category SetC.

Every coequalizer is an epimorphism, a consequence of the uniqueness requirement in the definition of coequalizers. It follows in particular that every cokernel is an epimorphism. The converse, namely that every epimorphism be a coequalizer, is not true in all categories.

In many categories it is possible to write every morphism as the composition of a monomorphism followed by an epimorphism. For instance, given a group homomorphism f : G → H, we can define the group K = im(f) = f(G) and then write f as the composition of the surjective homomorphism G → K which is defined like f, followed by the injective homomorphism K → H which sends each element to itself. Such a factorization of an arbitrary morphism into an epimorphism followed by a monomorphism can be carried out in all abelian categories and also in all the concrete categories mentioned above in the Examples section (though not in all concrete categories).

Related concepts

Among other useful concepts are regular epimorphism, extremal epimorphism, strong epimorphism, and split epimorphism. A regular epimorphism coequalizes some parallel pair of morphisms. An extremal epimorphism is an epimorphism that has no monomorphism as a second factor, unless that monomorphism is an isomorphism. A strong epimorphism satisfies a certain lifting property with respect to commutative squares involving a monomorphism. A split epimorphism is a morphism which has a right-sided inverse.

A morphism that is both a monomorphism and an epimorphism is called a bimorphism. Every isomorphism is a bimorphism but the converse is not true in general. For example, the map from the half-open interval [0,1) to the unit circle S1 (thought of as a subspace of the complex plane) which sends x to exp(2πix) (see Euler's formula) is continuous and bijective but not a homeomorphism since the inverse map is not continuous at 1, so it is an instance of a bimorphism that is not an isomorphism in the category Top. Another example is the embedding Q → R in the category Haus; as noted above, it is a bimorphism, but it is not bijective and therefore not an isomorphism. Similarly, in the category of rings, the maps Z → Q and Q → R are bimorphisms but not isomorphisms.

Epimorphisms are used to define abstract quotient objects in general categories: two epimorphisms f1 : X → Y1 and f2 : X → Y2 are said to be equivalent if there exists an isomorphism j : Y1 → Y2 with j f1 = f2. This is an equivalence relation, and the equivalence classes are defined to be the quotient objects of X.

Terminology

The companion terms epimorphism and monomorphism were first introduced by Bourbaki. Bourbaki uses epimorphism as shorthand for a surjective function. Early category theorists believed that epimorphisms were the correct analogue of surjections in an arbitrary category, similar to how monomorphisms are very nearly an exact analogue of injections. Unfortunately this is incorrect; strong or regular epimorphisms behave much more closely to surjections than ordinary epimorphisms. Saunders Mac Lane attempted to create a distinction between epimorphisms, which were maps in a concrete category whose underlying set maps were surjective, and epic morphisms, which are epimorphisms in the modern sense. However, this distinction never caught on.

It is a common mistake to believe that epimorphisms are either identical to surjections or that they are a better concept. Unfortunately this is rarely the case; epimorphisms can be very mysterious and have unexpected behavior. It is very difficult, for example, to classify all the epimorphisms of rings. In general, epimorphisms are their own unique concept, related to surjections but fundamentally different.

See also

References

- Adámek, Jiří, Herrlich, Horst, & Strecker, George E. (1990). Abstract and Concrete Categories (4.2MB PDF). Originally publ. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60922-6. (now free on-line edition)

- Bergman, George M. (1998), An Invitation to General Algebra and Universal Constructions, Harry Helson Publisher, Berkeley. ISBN 0-9655211-4-1.

- Linderholm, Carl (1970). A Group Epimorphism is Surjective. American Mathematical Monthly 77, pp. 176–177. Proof summarized by Arturo Magidin in [1].

- Lawvere & Rosebrugh: Sets for Mathematics, Cambridge university press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-80444-2.